Stream Processing, Transactions, Crash Resilience in p2panda

✉️ Posted on 09.07.25

🖊️ Written by adz

In peer-to-peer applications, processes can crash, fail or be interrupted at any point. This occurs not only as a result of losing connectivity with other peers, abruptly ending a stream of data, but also due to the fact that the process itself doesn’t run on a stable, highly-available server but on a mobile phone, laptop or other edge device. Whenever the user decides to “swipe up” and move the app into the background, or the operating system decides not to allocate any more resources to the process, we can’t guarantee that whatever we started will end well. And of course, despite our best efforts as developers, bugs can always happen.

Why are crashes dangerous for applications and especially peer-to-peer ones?

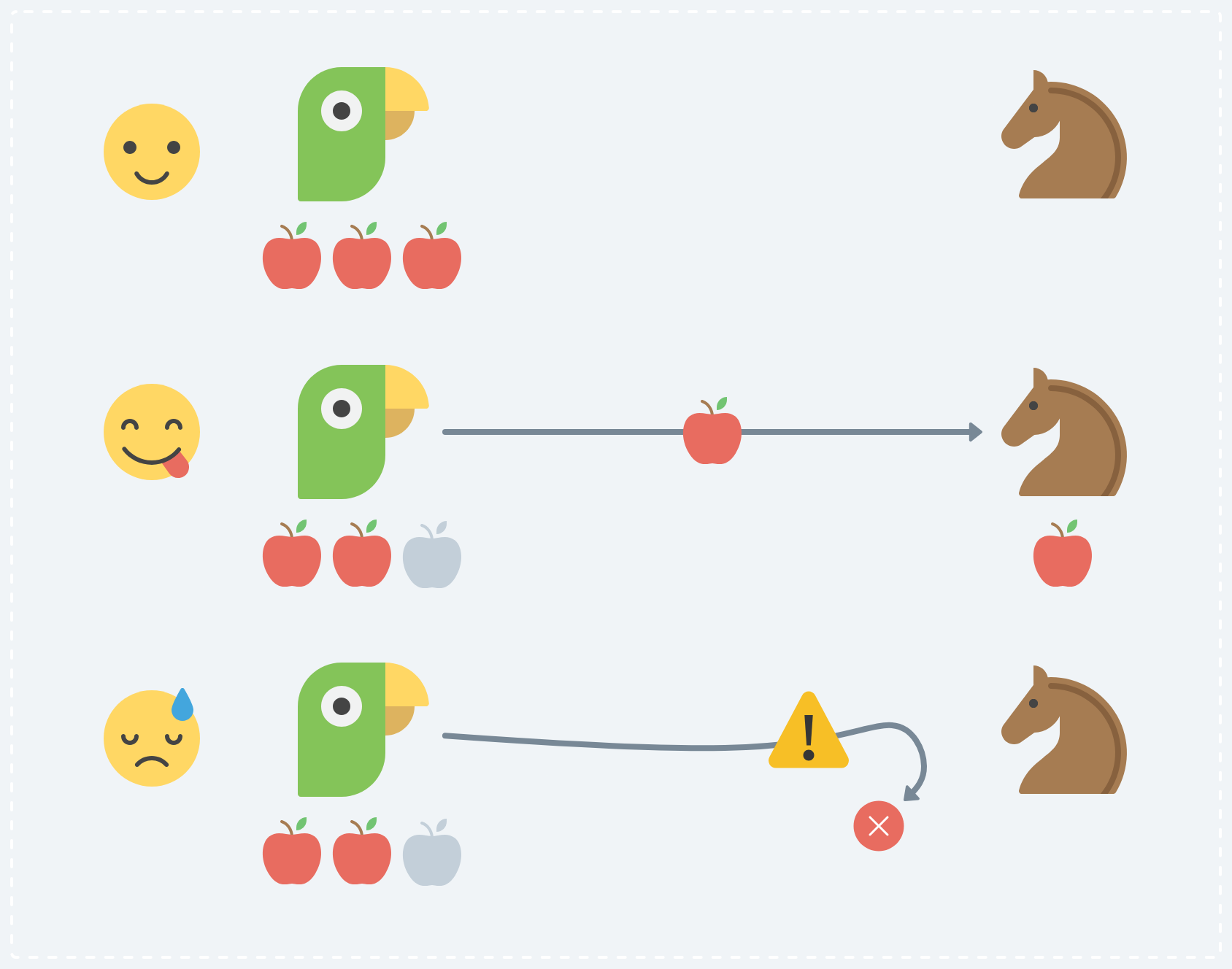

A classic example: Parrot wants to send one apple to Horse. Parrot starts the transaction and removes an apple from their store. Horse receives the apple and adds it to their store. If one of the processes crashes on either Parrot’s or Horse’s side, we might end up with a situation where Parrot’s state has one less apple and Horse’s has none.

An example of a failed transaction where Parrot will loose an apple and Horse will never receive it.

We never want to end up in a situation where a failure like that leads to the app hanging in an invalid state. Trying to recover a “broken” peer is especially hard when doing things without any central coordination.

This blog post is about the strategies and design ideas we’re exploring in p2panda to make p2p applications resilient to critical failures, for both system- and application layers.

Processing system- and application data

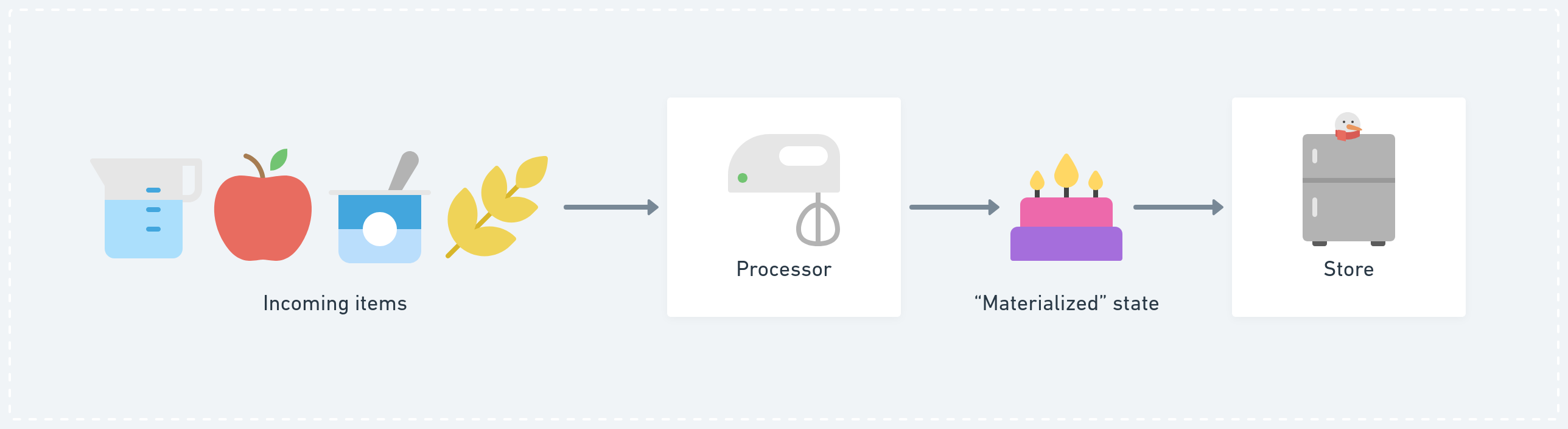

Processes usually change their internal state when receiving new data or input. Peers observe messages on a network and process them based on a set of rules. Message processing results in a new state which then gets moved into a store or database.

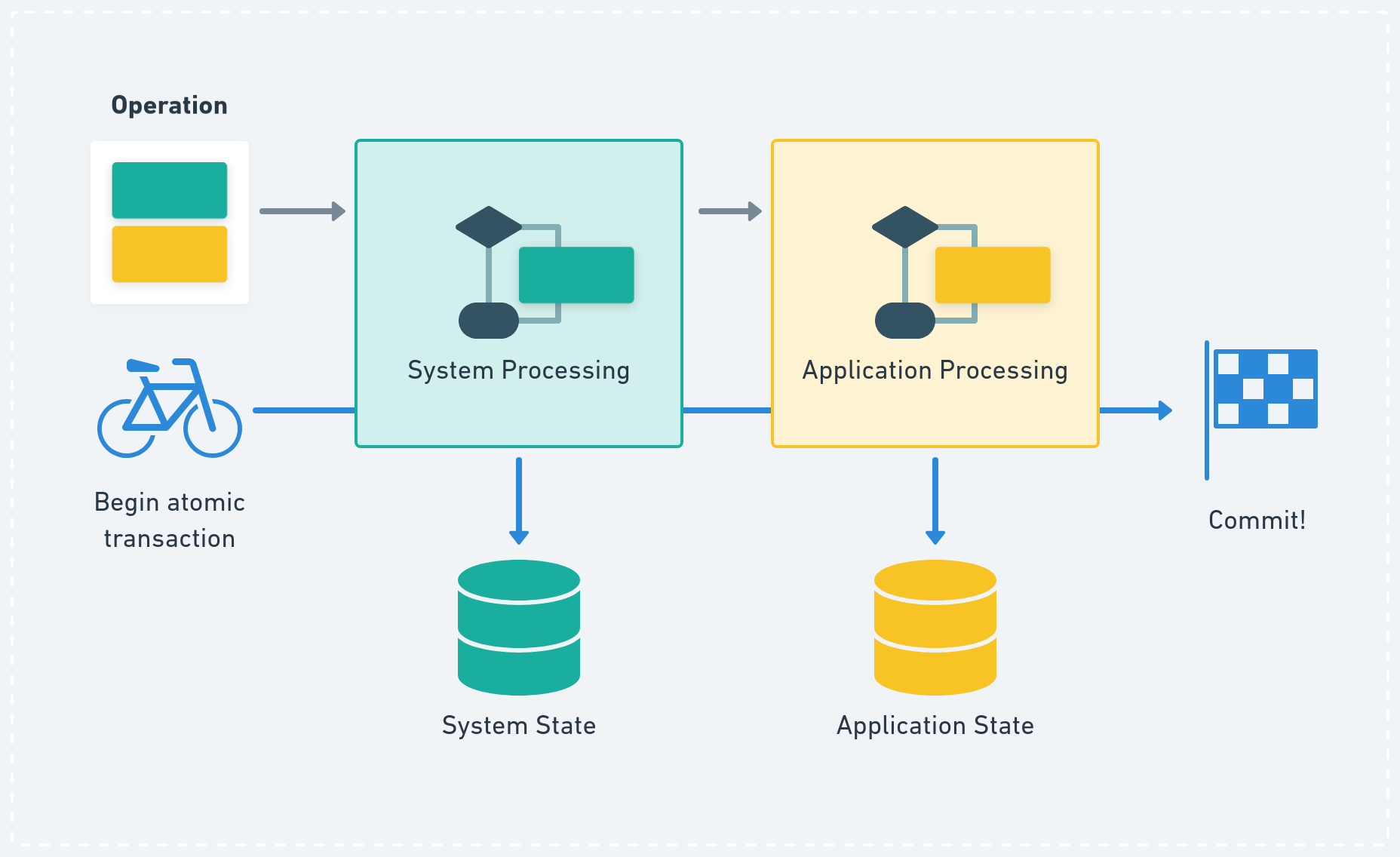

Regular processing pipeline.

What is different from more traditional client-server models is that in peer-to-peer systems every single peer needs to process the incoming data and store the materialised or indexed state by itself, instead of relying on a server doing the “hard work” and the “lightweight” client cheaply querying the materialised result.

In p2panda it is possible to model application data and the processing of it however you like. We have observed three emergent “patterns” for doing so:

- Peers send messages to each other which simply need to be stored in a database, for example chat messages or “social media” posts. Not much processing needs to be done here.

- Peers send State- or Operation-based CRDTs (Conflict-free replicated data types) to each other. These “updates” form a new CRDT state which allows all peers to eventually converge to the same state. Applications like Reflection follow this pattern.

- Peers send events to each other which are processed based on a form of “event sourcing” logic. This can also be understood as event or stream processing (depending on where you come from). By re-processing all events we can re-construct the state again. Applications like Toolkitty follow this pattern.

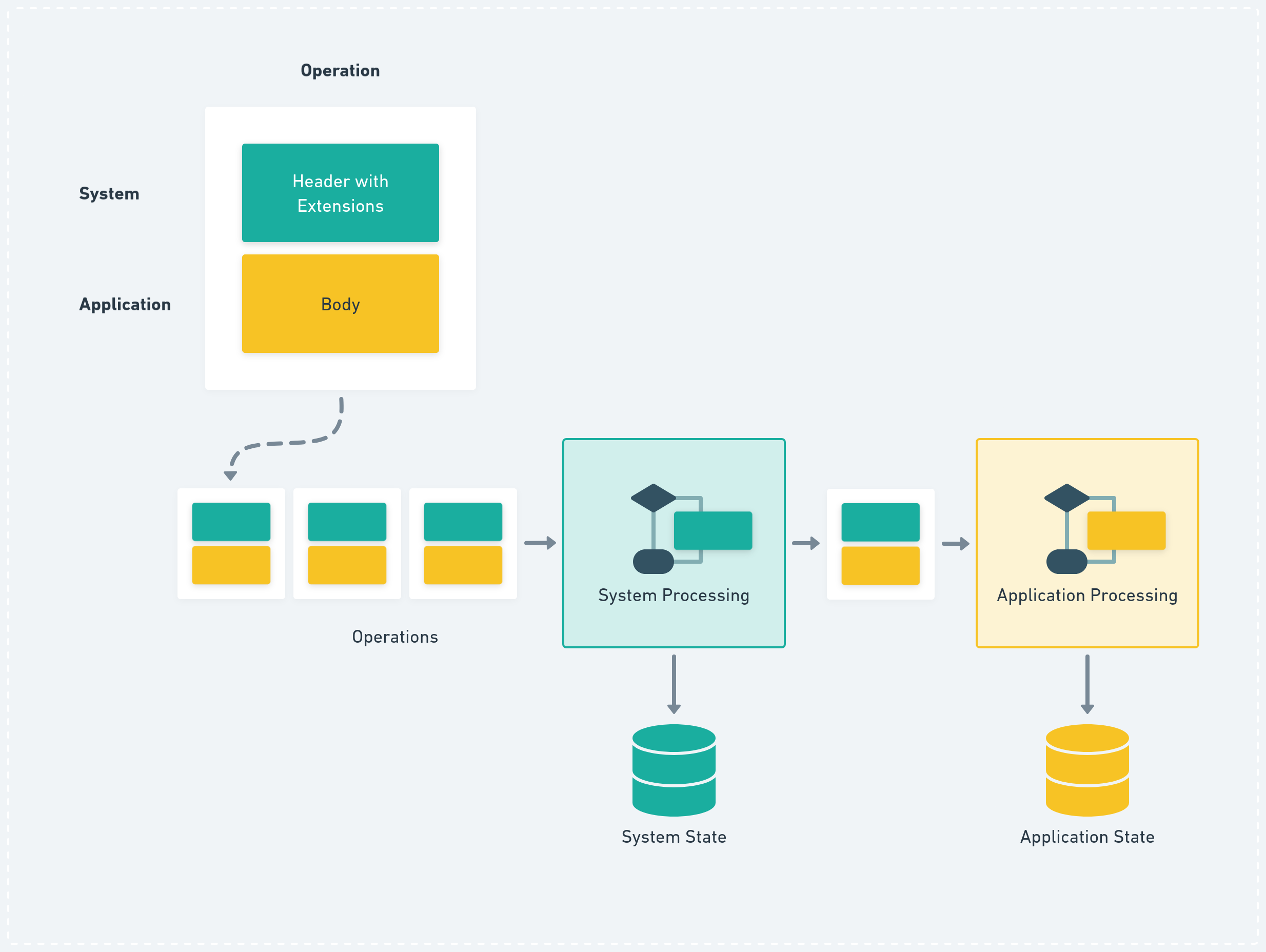

In most application contexts there is underlying system data which needs to be processed before we process our application data.

In p2panda we offer different building blocks as part of the system layer which solve a collection of common challenges in p2p systems, for example: Authentication, Integrity Guarantees, Ordering, Deletion, Garbage Collection, Offline-First, Access Control, Roles Management and Group Encryption.

Information required to coordinate these system-related data-types or protocols is usually transmitted as part of the Header of every p2panda Operation being sent. This Header contains information to describe append-only logs, DAGs giving us partial ordering, signatures, pruning mechanisms, key agreement, capabilities etc. Next to the Header the Operation also contains a Body; this is where the previously-mentioned application data goes. The exact shape of the data is defined by the application but it must be encoded as bytes for inclusion in the Body.

Operations processed first on system- then on application layer. The system layer uses data stored in the Header of the Operation for processing, the application layer is mostly interested in what’s in the Body.

Whenever a p2panda Operation arrives at a peer we need to separate the system- and application concerns and handle them one after another. First we look into the Header, process it and adjust our system state accordingly. Has this author been invited to an encrypted group context? Is this author allowed to write to this document? Did this Operation arrive out-of-order and do we need to wait before we can proceed with it? Can we decrypt the Body?

After all of the system processing and checks have taken place, we can finally “forward” the Operation to the application layer which is controlled by the developers who want to build anything on top. Here we can only guess what will happen, but let’s assume that some sort of processing will also be required and whatever comes out of it will land in some application state, potentially persisted in a database like SQLite.

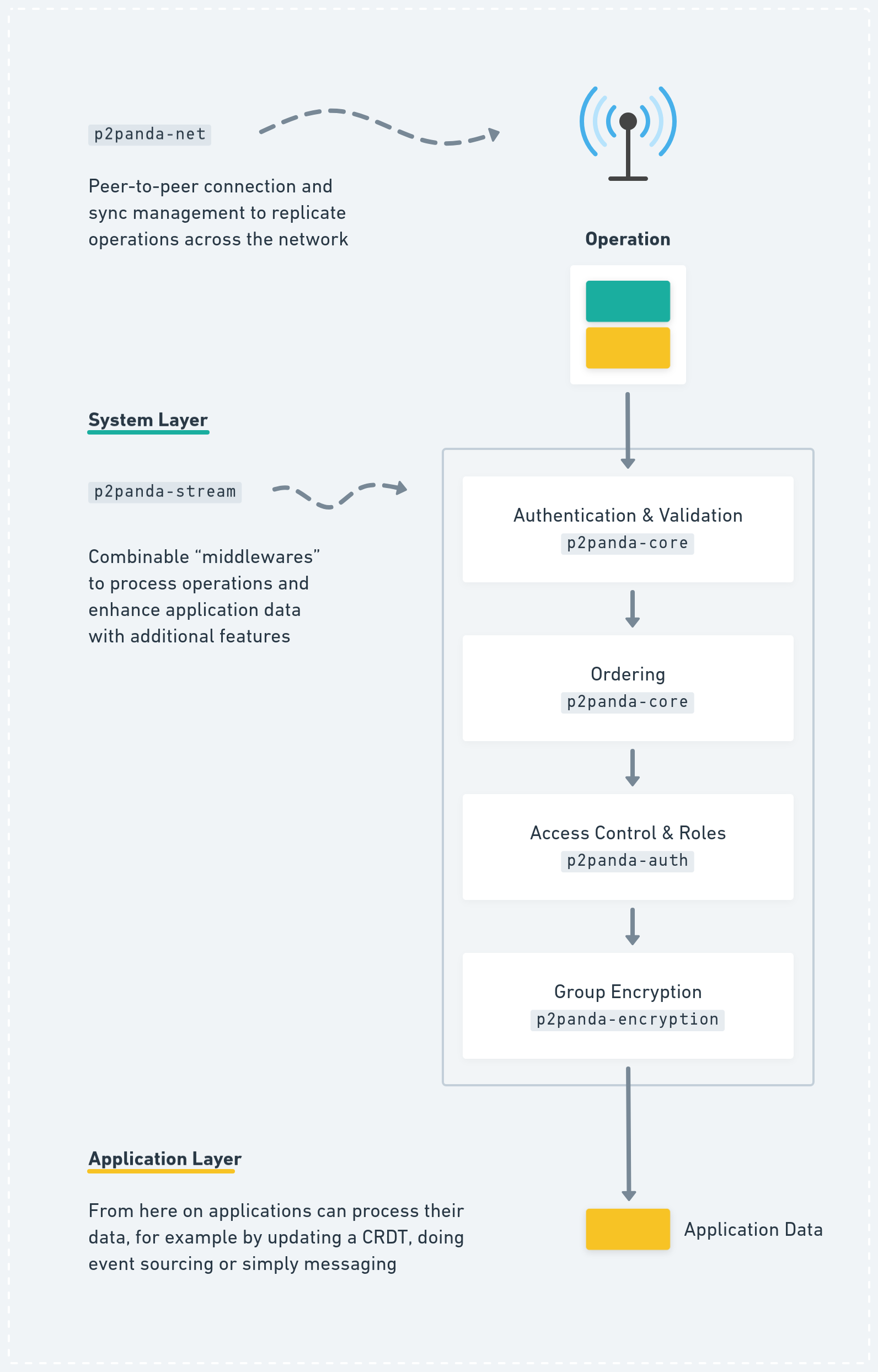

Our goal is to allow developers to combine and “stack up” different processing flows for their individual application needs. Does your application need permission management? Add p2panda-auth to the processing pipeline!

This is very similar to middleware APIs in classical HTTP frameworks like Express or Tower where different “features” can be stacked up on top of each other for every incoming “request”.

Stacking system layers like “middlewares” in p2panda.

While we’re building completely p2panda-independent data-types and protocols, for example around access control in p2panda-auth or group encryption in p2panda-encryption, we offer a common ground with p2panda-stream where these solutions can easily be combined and integrated into every application’s pipeline.

The name and APIs are still in flux but we believe that this gives the most framework-independence and flexibility while allowing application developers to focus primarily on application-level concerns.

We’ve experimented with Rust Stream to express a “flexible” middleware API in our p2panda-stream crate but unfortunately Rust’s strict type system and exploding complexity and boilerplate around nested async calls and generics makes the use of it not enjoyable, and prone to bugs. Currently we’re exploring a more pragmatic approach with slightly less flexibility and significant better readability and ease of usage.

Why all of this introduction into the p2panda processing pipeline when talking about crash resilience? We see now that there are multiple state changes required before we even arrive at the application layer. In addition, we only really want to commit to the new state if the application finally says: “Yes, this operation was valid and everything is ok”. To achieve this guarantee we need to be able to express the processing of an operation across both layers as one single atomic transaction.

Atomic Transactions

There has already been a lot of thought put into making applications crash-resilient on state changes, for example when writing to a database. This is not an exclusive peer-to-peer problem to have; all applications need to take care of this, it is just a question as to whether or not developers actually do it.

Databases like SQLite or PostgreSQL try to handle exactly these cases by fulfilling certain properties which can be summarised as ACID. Martin Kleppmann once again gives an excellent introduction into these properties (and how they can be misunderstood).

The “A” in ACID stands for Atomicity and is exactly the property we are interested in for our systems. By grouping state changes into one atomic transaction we can guarantee that either all get executed at once, or none of them. If anything fails, the transaction is aborted and all changes are rolled back, as if they never happened.

Even before our data hits the actual database (like SQLite) we already need to worry about these things like atomicity, this is why building a p2p protocol can sometimes feel like re-inventing databases.

Here is an example of how to express an atomic transaction in SQL using the sqlx Rust crate, following our initial apple-sending example with Parrot and Horse:

// Initiate a single, atomic transaction using sqlx.

let mut tx = connection.begin().await?;

// Remove one apple from Parrot.

sqlx::query("UPDATE apples SET amount = 2 WHERE user = 'parrot'")

.execute(&mut *tx)

.await?;

// Give Horse one apple.

sqlx::query("UPDATE apples SET amount = 1 WHERE user = 'horse'")

.execute(&mut *tx)

.await?;

// Finally "commit" all of these changes. They will be persisted

// from now on if nothing crashed until here.

tx.commit().await?;

In p2panda every incoming Operation begins a new atomic transaction which will be used for every state change or write to a database during processing. Finally we want to forward the same transaction object to the application layer so developers can continue writing to the database as part of the same transaction.

Atomic transactions in the processing pipeline.

This solves two important problems: First, we don’t want to end up with invalid state when a process crashes. Imagine that a chat message arrives, the system layer decrypts the data using the “Message Encryption” scheme of p2panda-encryption with double ratcheting, moves the ratchet forwards, writes the new encryption state to the database and due to a bug in the application layer everything crashes and we never save the plaintext. Now we potentially end up with a situation where the message will never be read. With this in mind, we don’t want to persist any changes to the database until the final application layer “committed” the transaction, making sure that everything until then succeeded.

The second issue solved is validation: Applications should always have the last say as to whether or not they want to reject an operation based on their own application validation logic and social protocols. Even when nothing fails, an application can choose to not commit to the new state. This might occur when the application protocol has been violated due to invalid encoding or offensive content has been published. In such cases, users many not want to persist any operations in our database, nor to commit to any state changes triggered by them.

APIs

We don’t want to burden application developers too much, at the same time we can see that caring about atomic transactions is crucial for rolling out any robust p2p application.

As part of the p2panda-store crate we’re currently preparing traits (Rust interfaces) to implement state handling with atomic transactions against any possible database implementation. You can see the related PR here.

With this trait design we stay flexible with the final choice concerning what database your application would like to use (in-memory, SQLite, redb, etc.) while keeping the atomicity guarantees.

The API design clearly separates “read” queries from “writes”, as the latter is the only one actually changing state and thus needing to be placed inside an atomic transaction.

Inspired by sqlx we follow a very similar API approach to express writing state to a database inside of transactions and committing them:

// Initialise a concrete store implementation, for example for

// SQLite. This implementation implements the WritableStore

// trait, providing it's native transaction interface.

let mut store = SqliteStore::new();

// Establish state, do things with it.

//

// User and Event both implement the WriteToStore trait for the

// concrete store type SqliteStore.

let octopus = User::new("Octopus");

// To retrieve state from the database we can read from it via

// a trait interface which was implemented against SqliteStore.

//

// How this trait exactly looks like was defined by whoever

// defined what a "User" is.

let horse = store.find_user("Horse").await?;

let mut event = Event::new("Ants Research Meetup");

event.register_attendance(&octopus);

event.register_attendance(&horse);

// Persist new state in database as part of a transaction.

let mut tx = store.begin().await?;

octopus.write(&mut tx).await?;

horse.write(&mut tx).await?;

event.write(&mut tx).await?;

tx.commit().await?;

There are different possible approaches to design state handling around transactions and our traits. We’re exploring multiple options right now, for example pure functions.

Pure functions are functions which do not have any side-effects; they will never write to a database when being called and instead return a new state object. The combination of transactions and Rust’s strict borrow checker allows us to express state handling quite neatly (and we did it a lot inside our p2panda-auth and p2panda-encryption crates), for example:

// Retrieve current group state from database.

let state = store.group_by_id(&group_id).await?;

// Create a new group state in "pure function style".

let new_state = Group::add_member(state, &member_id).await?;

// Persist new group state as part of atomic transaction.

new_state.write(&mut tx).await?;

Replaying operations with a stream controller

It is important to note that after a process has crashed and restarted, we want to “re-play” any operation which never completed, otherwise our application will not have a chance to recover from the crash and the operation will be lost.

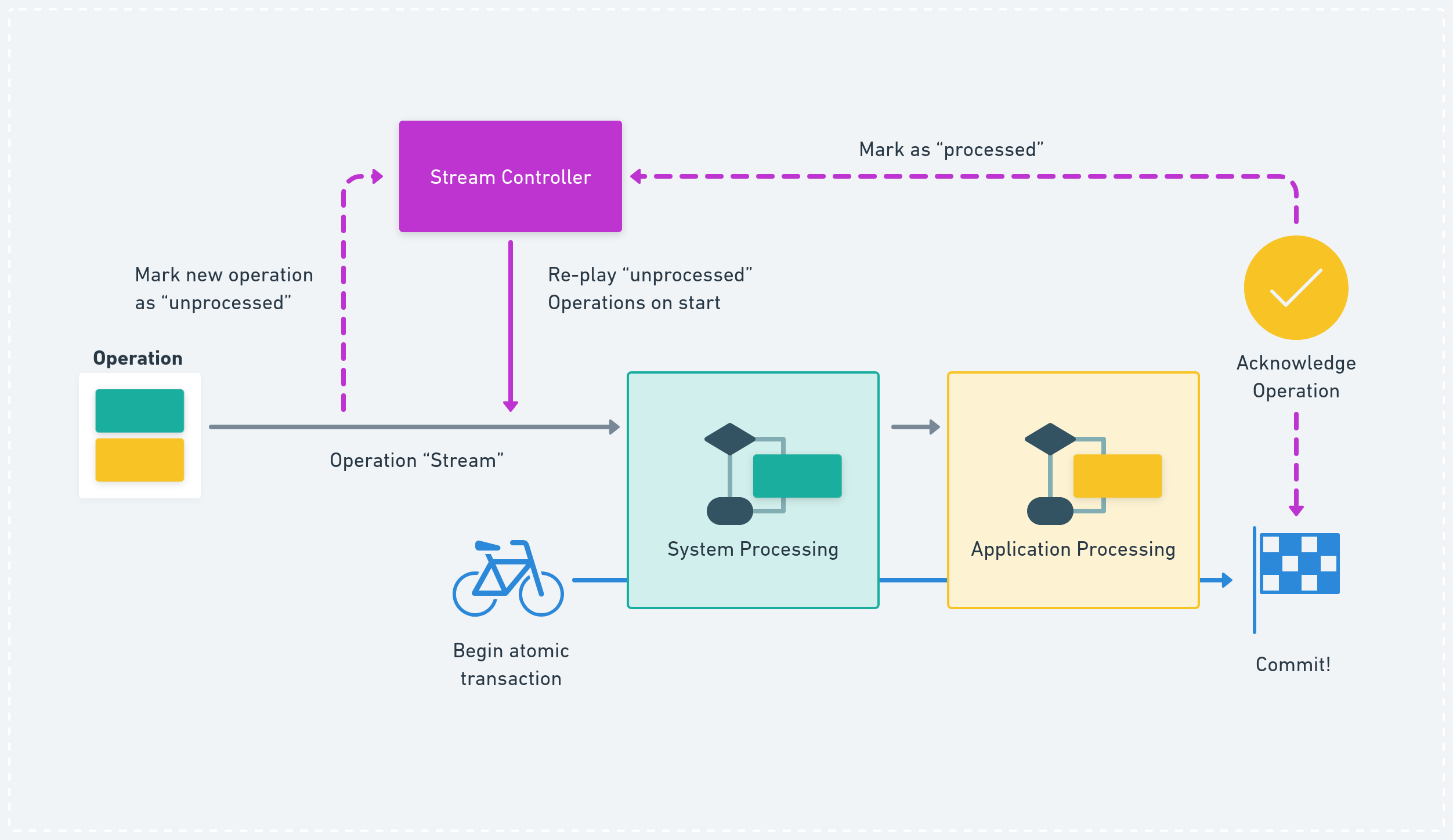

As part of p2panda-stream (the stackable middleware pipeline) we’re planning on integrating a stream controller which allows re-playing “unprocessed” operations by default and manually re-playing all or a range of operations from a certain point (defined by logical or wall-clock time) or “topic” (grouping operations defined by the application) when required.

The stream controller can be neatly combined with atomic transactions. Every operation needs to be “acknowledged” by the application layer at the end of every processing. This signals to the controller that the operation can now be marked as “processed”. Now we can finally commit the atomic transaction with all state changes caused by that operation and we don’t need to re-play it whenever the process starts again.

Processors usually need to have idempotency guarantees; this can be difficult to reason about when the codebases and data types get complex. Processing an operation twice might lead to invalid state (for example, Horse ending up with two apples when only one was sent). By combining transactions with a stream controller we can guarantee that the state produced by processing an operation is only ever committed once.

A stream controller design is already implemented as part of the Toolkitty peer-to-peer application and we now want to move the ideas into our official libraries.

Stream controller with atomic transactions in the processing pipeline.

From our previous experience of releasing peer-to-peer applications like Meli we can also utilise a stream controller for rolling out app updates with breaking changes or emergency bug fixes. If a schema or data type has changed we might need to wipe some database state, re-play all available operations and re-instantiate the database with the breaking change or bug fix in place. This is a useful feature to have around in case an application ever needs it.

The p2panda node

p2panda is a project which didn’t start by specifying a “perfect system” before building it. We begin by exploring patterns and ideas while vertically integrating them into user applications through collaboration with other teams. At times this makes it challenging to explain what p2panda is and how to get started, as we’re deep down in exchanging with application developers and reasoning about the constantly changing APIs.

However, in all of this we can see useful patterns emerging, such as clear separation of system- and application concerns, access control and roles, group encryption, multi-device support, message ordering, transactions, stream processing with “stackable” middleware APIs and stream re-plays - and we want to move all of this into one unified p2panda-node with an RPC API and a robust p2p networking and sync layer underneath.

All of this takes place on higher “integration layers”, while still keeping all “low-level” code (for example, group encryption) clearly separated, so whoever wants to just use one particular feature built by p2panda will not need to follow the same design.

For everyone who wants to have a complete peer-to-peer backend with robustness and security guarantees, we’re gradually moving towards the release of p2panda-node. We will then be able to replace all system-level “custom” integration code with a more unified solution for some of our applications. Stay tuned!