Local-First group- and message encryption in p2panda

✉️ Posted on 24.02.25

🖊️ Written by adz

With the generous support of NLNet and a pending audit by Radically Open Security we’re aiming at releasing our Rust crate p2panda-encryption towards Spring 2025!

This library will offer group encryption compatible with any data type, encoding format or transport, made for p2p applications which do not rely on constant internet connectivity. Similar to our other crates, we aim to make our implementation independent of the rest of p2panda while providing optional “glue code” to integrate it in into the larger p2panda ecosystem. With this design we’re adding another building block for secure and private p2p applications to our p2panda collection.

p2panda-encryption manages group membership with a Conflict-Free Replicated Data-Type (CRDT) and two different group key-agreement and encryption schemes. The first scheme we simply call “Data Encryption”, allowing peers to encrypt any data with a secret, symmetric key for a group. This will be useful for building applications where users who enter a group late will still have access to previously created content, for example private knowledge or wiki applications or a booking tool for rehearsal rooms. A member will not learn about any newly created data after removing them from the group since the key gets rotated on member removal or manual key update. This should accommodate for many use-cases in p2p applications which rely on basic group encryption with post-compromise security (PCS) and forward secrecy (FS) during key agreement.

The second scheme is “Message Encryption”, offering a forward-secure (FS) messaging ratchet, similar to Signal’s Double Ratchet algorithm. Since secret keys are always generated for each message, a user can not easily learn about previously created messages when getting hold of such key. We believe that the latter scheme will be used in more specialised applications, for example p2p group chats, as strong forward-secrecy comes with it’s own UX requirements, but we are excited to offer a solution for both worlds, depending on the application’s needs.

Together with our work towards access control we’re at the end of a longer research and implementation phase and we’re excited to publish a solution to secure data encryption and messaging in p2panda soon.

This blog post is the first announcement of p2panda-encryption and we want to share our insights, learnings and design from this research and implementation phase.

Encryption in p2p applications

If we entrust our private data to specific peers we are always directly connected with, we can rely on transport encryption only. This works as soon as we can cryptographically verify that the other peer is really the authentic one we trust exchanging data with. We can, for example, keep a “friends” list of public keys around and only allow establishing a connection if their signatures match, or we rely on a symmetrical secret (Pre Shared Key or PSK) every peer needs to know to establish a connection. Self-signed TLS Certificates in QUIC or one of the many Noise Protocol patterns allow us to establish that trust towards each other on transport level. Peer-to-peer protocols like Cable elegantly specify such a system.

As soon as we don’t want our network to theoretically have access to every message we author (even if it is our friends), or if we want to relay our private messages through “untrusted” peers or server admins, we need some sort of data encryption scheme.

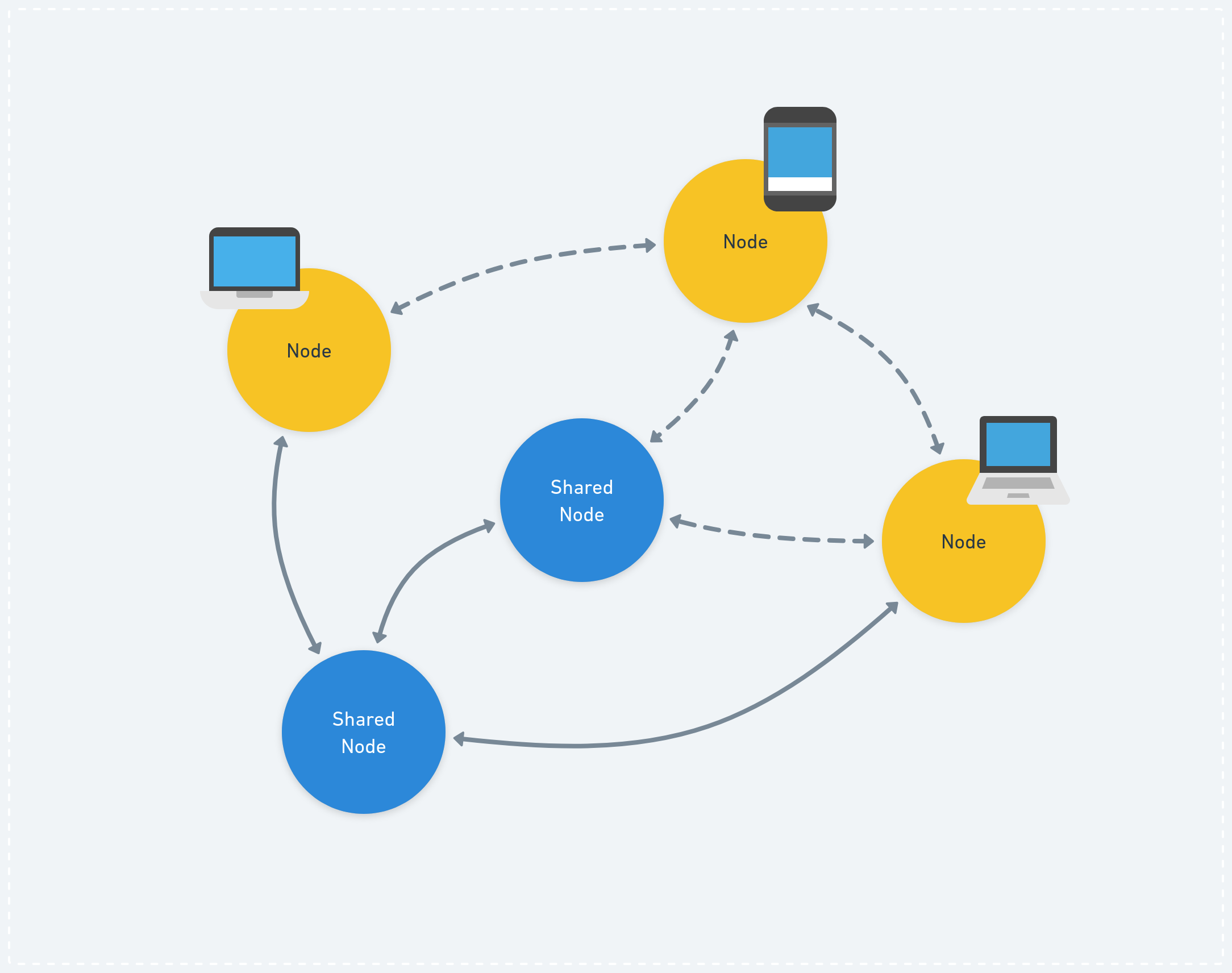

In p2panda we are exploring solutions where we can work with “shared” nodes in the future: These are “always-online” servers which can be shared among friends or used only personally for different devices. They sync up with “leaf” or “edge” nodes (which can be offline and change location all the time) and keep the data as fully encrypted blobs, ideally with almost no metadata attached.

Nodes can run on mobile devices, laptops and desktop computers. They sync data with other nodes whenever they are online. “Shared Nodes” are instead always online and provide data when all other nodes are unavailable. The crucial point here is that this system would even work when no “Shared Nodes” are available, data might just flow more slowly.

Shared nodes help us to sync up on the latest data, even when all nodes are currently offline. The data itself can be ephemeral and automatically wiped from the server’s database after a while. The important thing is: We want the network to continue functioning as normal even when no shared nodes are involved; they are an enhancement to the system, but not a requirement.

Delta Chat already successfully experiments with this concept with their so-called Chatmail servers, Next Graph provides a similar 2-Tier solution with Broker nodes and Ink & Switch is thinking along the lines of peers with pull permissions. These are servers which are allowed to “pull” or sync your data, but they will not be able to read it’s contents, because it’s encrypted!

If we can dream wildly we can even see a “Shared Nodes System Setting” one day, built straight into our operating system! We define which nodes we want to maintain a connection with and entrust our (encrypted) data to. They can be shared with friends, family, collectives, etc. - but that’s for the long run.

Another factor is that we don’t want anyone to learn about our actions or data, even if we consider them our “trusted” circle. Just because Billie, Claire and Davie are best friends, Davie doesn’t need to always be able to see what Billie and Claire talked about. There are many ways to model such a system, but data encryption can be one of them.

Shared Nodes, Delivery Services, Caching Layers, or however you want to call them, are already implemented and successfully used and deployed in production. Still, we are in need of a solution which works in a more decentralised setting, that is, even when no intermediate peers or “always-online nodes” are available, we want group encryption to always work, even when your node is running on a smartphone.

Exciting developments

There is exciting research and experimentation in this direction, most recently Beehive explores a TreeKEM-based data encryption scheme for local-first protocols. Organising the shared secrets in form of a tree provides similar efficiency to maintaining larger groups with Messaging Layer Security Protocol (MLS). Similar to our “Data Encryption” scheme, Beehive is forward-secure for the key-agreement part and not forward-secure for the final data encryption. It aims at an integration with Automerge and a new sync protocol for DAG-based data-types called Beelay.

Auth of Local First Web has an elegant solution to accommodate for both authenticated group membership management and group encryption by building a DAG with cryptographically secure pointers which solves a large part of maintaining potentially forked group membership states and giving a secure way to verify that a member has actually been allowed to perform a specific group operation, for example adding or removing a member. Check out their excellent blog post for an overview.

The p2panda team have looked deeply into MLS and the OpenMLS Rust implementation in the past. While different academic (for example CoCoA, DeCAF or FREEK) and practical attempts, like Matrix Protocol, are being made right now to make these algorithms work in a more p2p setting, it is still too far off to simply adopt this technology, even though we would prefer to rely on known IETF standards and widely-used implementations like OpenMLS.

That being said, forks are also a thing in centralised applications (caused by bugs, race conditions, connection errors etc.) and even protocols like MLS need to look into fork-resilience and concurrency issues at one point. On this front we are definitely excited to follow the developments, with research around the FREEK protocol being probably the most promising.

We have been particularly inspired by the Key Agreement for Decentralized Secure Group Messaging with Strong Security Guarantees (DCGKA) paper by Matthew Weidner, Martin Kleppmann, Daniel Hugenroth and Alastair R. Beresford (published in 2021) which is the first paper we are aware of which introduces a PCS and FS encryption scheme with a local-first mindset. On top there’s already an almost complete Java implementation of the paper, which helped with realising our Rust version.

The paper formed the initial starting point of our work. In particular, we followed the Double-Ratchet “Message Encryption” scheme with some improvements around managing group membership. We also carried over some of the ideas in the paper to accommodate for the simpler “Data Encryption” approach.

While not as performant as a TreeKEM solution for large groups (“thousands of members”) as in Beehive or MLS, we value the simplicity of the DCGKA protocol. The paper shows that DCGKA is performant for small- to mid-size groups of ca. 128 members, similar to Signal. We are also excited to share a strong forward-secure “Message Encryption” scheme in our crate, next to a minimal post-compromise secure “Data Encryption” variant with forward-secure key-agreement. On top we’re aiming at a solution which will be fully generic and useful for other projects without tying them too much to an existing framework, sync protocol, encoding or data type.

Peer-To-Peer challenges

When we can’t rely on any centralised point to deliver key material, ask an authority about group membership or a member’s permission, building a secure encryption scheme gets challenging. The main challenges we’ve identified are:

Ordering

Messages in peer-to-peer networks can arrive out-of-order or very late, especially when the network is highly fragmented and peers are offline for a long time. Extra care is required to make systems robust for these “pending” states where data is missing or incomplete.

Group membership

We always want to know from our perspective with whom we are interacting. Every peer needs to be able to verify if a member is inside a group or not and that they have permission to change the group’s state, for example if they sent us a message that they want to remove a member from the group.

This gets especially tricky if we can’t ask a “central authority” for the “right” group state or don’t have any explicit consensus algorithms in place to determine a common ground among distributed processes. In a p2p world like this, we need to be able to deal with and verify group state locally for each peer from their perspective and tolerate potentially forked groups.

This can happen when, for example, two members concurrently add another member to the group while they don’t know about each others operations. This leads to two different, valid versions of the group, even if it’s just temporary and they get merged eventually.

Metadata

Not all data is usually encrypted. When we talk about encryption, some information might still be in plaintext to allow efficient authentication, storage, routing or processing of the data. This is what we usually call “metadata”. The problem with this form of data is that, even if the actual application data is protected, the metadata can still be used to derive sensitive information about the sender, for example: “who is the receiver”, “when was it sent”, “how large is the file”, etc.

The main trade-off we can see is between an efficient syncing strategy and encrypting all metadata. As soon as we encrypt everything it will get harder and harder to effectively exchange data with another peer. On top we put a lot of trust into that peer as they can also send us a lot of garbage: We are happily receiving a lot of encrypted data, but after decrypting it find out that it contains invalid information.

Some protocols like Willow, for example, require a timestamp to be kept in plaintext in their metadata, while everything else is encrypted. This allows the set reconciliation sync strategy to still remain efficient as data items can be sorted by timestamp. On top it is possible to use “relative” timestamps (like 0, 1 and 2) not revealing too much about the actual, “absolute” time signature of these events.

For p2panda itself we are undecided yet if we will follow the Willow path (using set reconciliation for syncing over fully encrypted data) or go more towards the direction Beelay is taking with their Sedimentree sync strategy over DAGs. In any case, some information, either timestamp or the hashed pointers of the graph need to remain in readable plaintext.

Like this it will be possible to protect all other information, including public keys, signatures etc. if necessary. This doesn’t come for free and puts more pressure on other parts of the system (validation, buffering, ordering, etc.).

Because of the generic nature of p2panda-encryption we will not dictate how metadata is treated in your data-type, as this is ultimately a routing, sync and application concern. However we propose an off-the-shelf solution which will find a compromise when integrating with the other p2panda crates, header extensions our multi-writer- and append-only log data types.

Post-compromise security (PCS)

When a member got removed from a group, it still takes a while until all members are aware of that removal. Not knowing about someone’s removal, some members will still continue to encrypt messages towards them as from their perspective the member is still in the group.

This is also a problem in centralised group encryption schemes, but here we have a centralised server and an “always connected” setup where clients usually learn very quickly about a member’s removal.

In a decentralised setting this information spreads slower, thus leaving the group in a transitional “post-compromise” state for longer. Only once the last member has synced up and received the removal event can we consider the group to be fully “healed”.

Members who learned about the removal are already secure and can safely continue to communicate; there is no need for the whole group to completely heal before others can continue.

One solution is to have always-online nodes around which help spreading this sort of information faster. Additionally we can make the key rotation more efficient, which means that the group in itself needs less messaging round-trips before being healed. In p2panda-encryption we are using the 2SM Key-Agreement Protocol, as proposed in the DCGKA paper, which optimises the group healing process to O(n) steps instead of O(n^2). In TreeKEM based systems we can rotate the keys in O(log(n)) steps so the group can heal even faster.

Forward secrecy (FS)

Allowing peers to use a key only once to encrypt data and drop it instantly after receiving and decrypting a message successfully allows them to be protected against attacks where a malicious actor can’t learn about previous messages when they get hold of such a key. This is called forward secrecy (FS) and is implemented in it’s strongest form in protocols such as Messaging Layer Security (MLS) or Signal.

Forward secrecy is a notoriously hard to grasp concept. It gives us additional security guarantees but also increases the complexity of both the protocol and implementation. It requires extra care to accommodate for such a system when integrating it into an application.

The largest challenge we see is the reliance on a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) when deploying FS encryption in decentralised systems as peers rely on “pre-keys” to establish the initial, commonly shared secrets when beginning to message each other (key agreement handshake). These pre-keys need to be known by each peer beforehand.

Some applications might have very strong forward secrecy requirements and only allow “one-time” pre-keys per group during key agreement handshake. This means that we can only establish a FS communication channel with a peer if we reliably made sure to only use the pre-key exactly once, which is hard to guarantee in a decentralised setting. If we don’t care about very strong FS we can ease up on that requirement a little bit and tolerate re-use with longer-living pre-keys which get rotated frequently (every week for example).

A solution for very strong forward secrecy, where we can make sure the pre-key is only used once, is a “bilateral session state establishment” process where peers can only establish a group chat with each other after both parties have been online. They don’t need to be online at the same time, just to be online at least once and receive the messages of the other party. This puts a slight restriction on the “offline-first” nature for peer-to-peer applications.

Another solution is to rely on always-online and trusted key servers which maintain the pre-keys for the network, but this puts an unnecessary centralisation point into the system and seems even worse. Publishing pre-keys via DNS might be an interesting solution to look into.

Puncturable Pseudo-Random Functions (PPRF) can help with preventing replay attacks where the security of a user gets weakened by making them “unknowingly” re-use the same one-time pre-key. This secures the owner of the pre-keys, but doesn’t solve eventual consistency of the senders, as they will not learn which message the receiver accepted first and which messages they rejected.

In p2panda-encryption we provide two different encryption schemes with variable strength of forward secrecy for different scenarios: “Message Encryption” gives strong forward secrecy like the Signal protocol and “Data Encryption” gives configurable forward secrecy during key agreement but no forward secrecy for application data itself - as members who join a group late are allowed to decrypt previously created data.

We believe there’s a place for applications in p2p with strong forward secrecy requirements with well-done UX, for example local-first messengers or applications using state-based CRDTs where no message history is required. We also can imagine applications running with both encryption schemes at the same time! Imagine a tool to organise your collective’s shared items where every member needs to have access to past records and thus encrypted with “Data Encryption”, while private messages between members are encrypted with stronger “Message Encryption”.

Lastly there should always be the option for an application to decide manually whenever it’s time to remove a decryption secret from the history, for example when data is simply not useful anymore. We keep this door open, even in the “Data Encryption” scheme.

p2panda Group Encryption

For a decentralised group encryption scheme we need the following parts:

- Causal Ordering of group operations (adding, removing, promoting, demoting members etc.).

- Group Management to reason about who the members of the group are from our perspective.

- Key Agreement to securely deliver secret keys to each member of the group.

- Encryption to finally secure application data with the group’s secret key material.

These parts are both required in p2panda’s “Data Encryption” and “Message Encryption” scheme, for most of them we can even re-use the same underlying mechanisms, cryptographic algorithms and data types.

Causal ordering

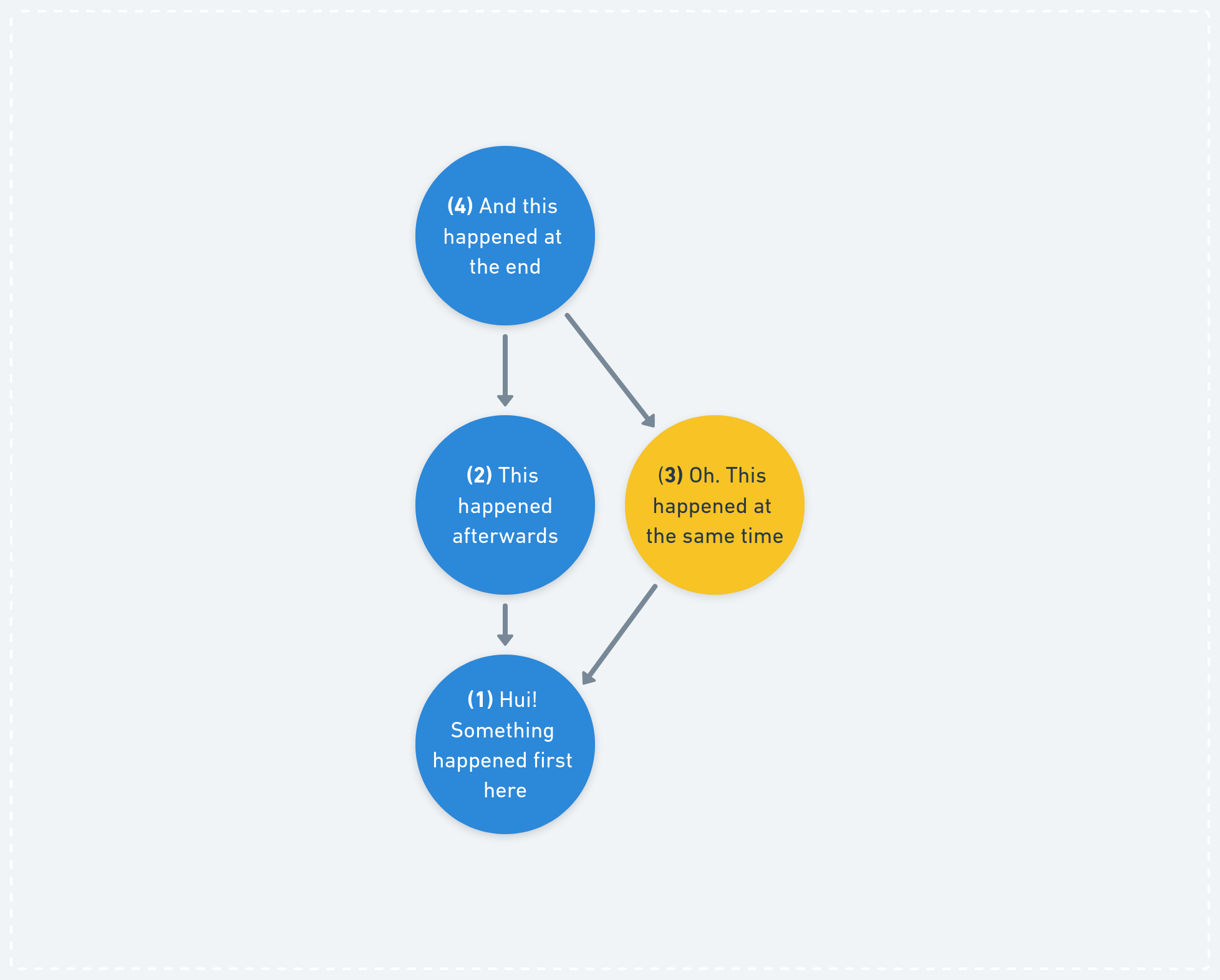

In p2panda we rely on our data type, the multi-writer directed acyclic graph (DAG) or “hash graph”, to establish a causal order of incoming operations, similar to a vector clock. Every operation points at the previous operation(s) it knows about by mentioning their cryptographic hash, which forms the graph. Now we can reason about whether an operation was sent before, after or at the same time as any other operation in the group.

We’re reading this graph from the bottom, starting at

1. Each circle represents an “operation” and the arrows point at the operation which was observed “before” it. This can be used to express causal orderings: We can see now if something happened before, after or at the same time. The operations2and3for example occurred at the same “logical” time.

The cool thing with this approach is that we:

- Gain a reliable way to reason about the causal ordering of events (partial ordering), even when they arrive at our node at random times.

- Already have this data type so we can simply re-use it for group membership management.

- Have a cryptographically secure way (through the unique hash function) to verify that we really observed one operation and that the authenticity of each operation is given, as they are signed by the author.

- Bonus point: Gain almost all the concurrency guarantees we need from this data type because a DAG can be understood as a CRDT in itself!

In our concrete p2panda-encryption Rust implementation we will not prescribe a specific ordering technique, so as to not tie developers too closely to our data types. Many p2p applications already have their own solutions for handling concurrency and, if not, we have these developers covered with our p2panda-core crate, providing the DAG data type, and causally ordered, “dependency checked” and buffered operation streams in p2panda-stream.

Group Management CRDT

The hash graph, mentioned above, can be used to verify if someone was allowed to perform a certain operation: we can use the cryptographic hashes and signatures of each signed operation to securely verify if a group operation was valid, by tracing back the “chain path” to the root of the graph and validating the operation at each step. “Was this member really assigned an admin role before and are they allowed to remove this other member now?”.

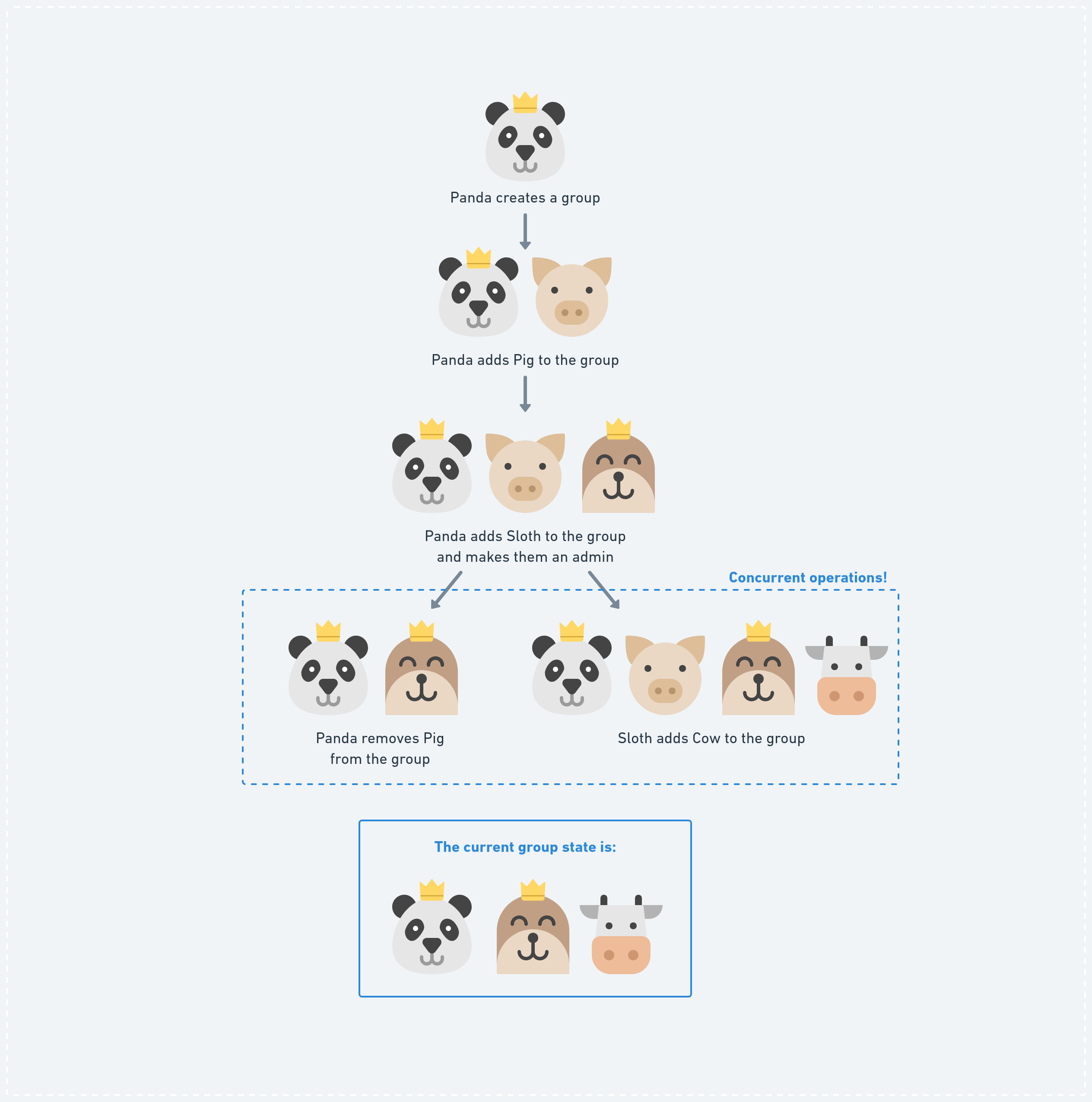

Here we flip the DAG around and start from the top! During each “operation” somebody changes the state of the group by adding or removing a member. With the causal history of our graph we can see how we can easily verify if a member was allowed to perform a certain operation. When two operations happened at the same logical time (Panda removes Pig and Sloth adds Cow), we need a method which can “merge” both “branches” and represent a final state which will be reached eventually by all peers as soon as they received both diverging operations.

This approach solves mostly all questions around managing group membership and checking permissions, except we need to be aware of some “special” concurrent cases. For example, what happens if two members remove each other at the same time or if a member got added by someone who was concurrently removed?

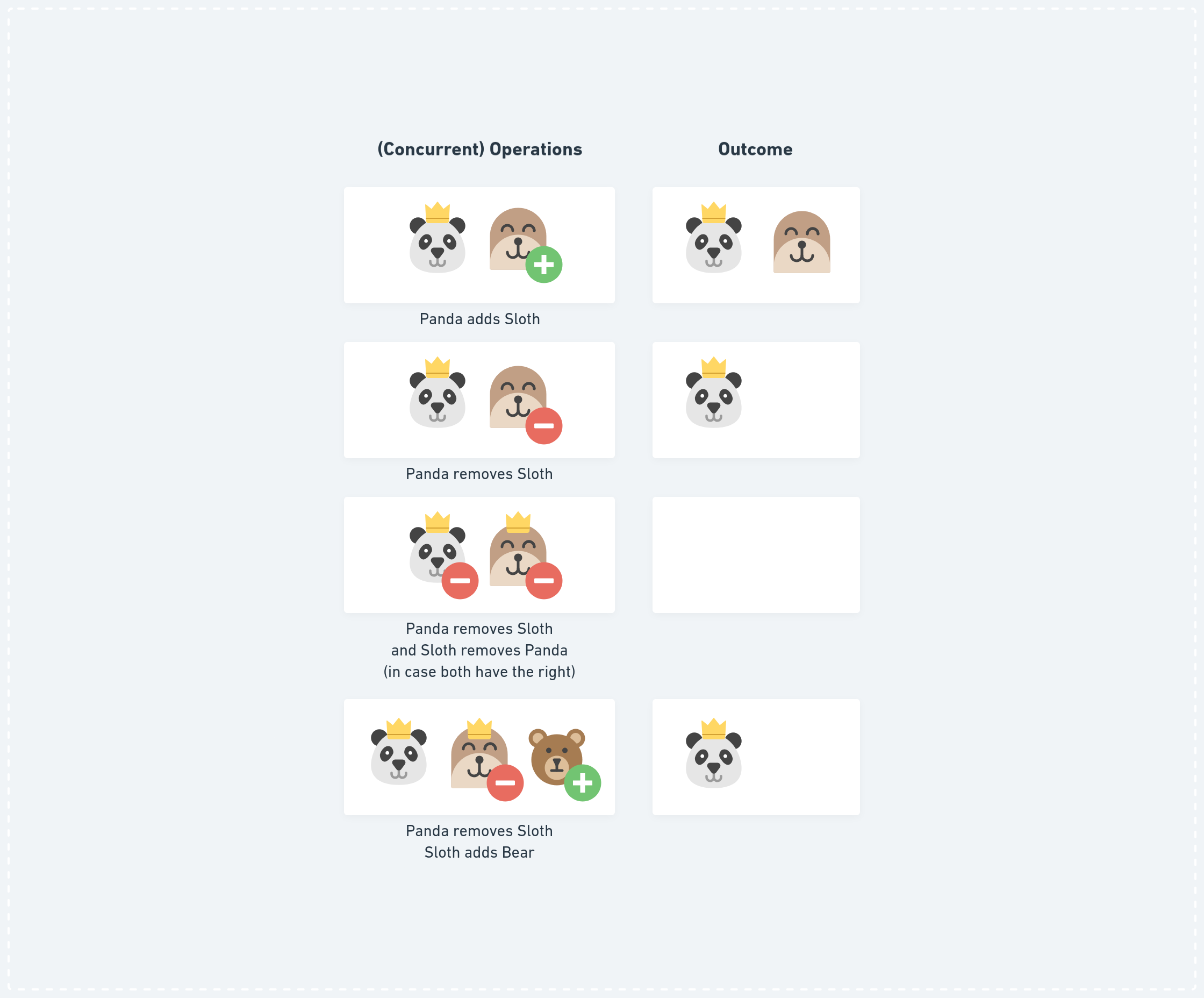

In p2panda-encryption we provide a default CRDT implementation which takes care of all of these situations by following a “strong removal” approach. This means that anyone who is removed can’t add any other member, even when they have been removed at the same logical time as when they added someone. If two members remove each other at the same time, they will both leave the group. This approach accounts for situations where it is more secure to remove everyone (for example, an attacker removing the admin while the admin tries to remove the attacker) and rely on social processes to re-establish a trusted group setting by re-adding members or starting a new group in worst case.

The last two scenarios show the “Strong Removal” CRDT logic. It might not always be desirable to remove all admins from a group if they try to remove each other. Different conflict resolution strategies can be chosen depending on the use-cases.

Since in Rust “everything is a trait” it is also possible to implement a different logic and apply other rules for different groups in these “conflicting” scenarios.

It is important to mention that we don’t provide a baked-in concept of “admins” or “moderators” as such but merely tools to express these relationships, so they can be designed by application developers based on their needs.

Key Agreement: Two-Party Secure Messaging (2SM)

Encrypting data for a whole group requires coordination, especially when it comes to sharing the secrets required to encrypt and decrypt the data. To make a group or another member aware of these secrets we need a “key agreement” protocol.

Key agreement in p2panda can be described in two phases, a first “key handshake” phase, which only occurs once, where we establish the shared secret for the first time. This happens when we are inviting a new member to a group and want them to learn about the secret key material. The second phase consists of subsequent “key rotations”. This can happen, for example, after we’ve removed a member from the group and we need to initiate a new key agreement to make sure the members who are still around learn about the new state.

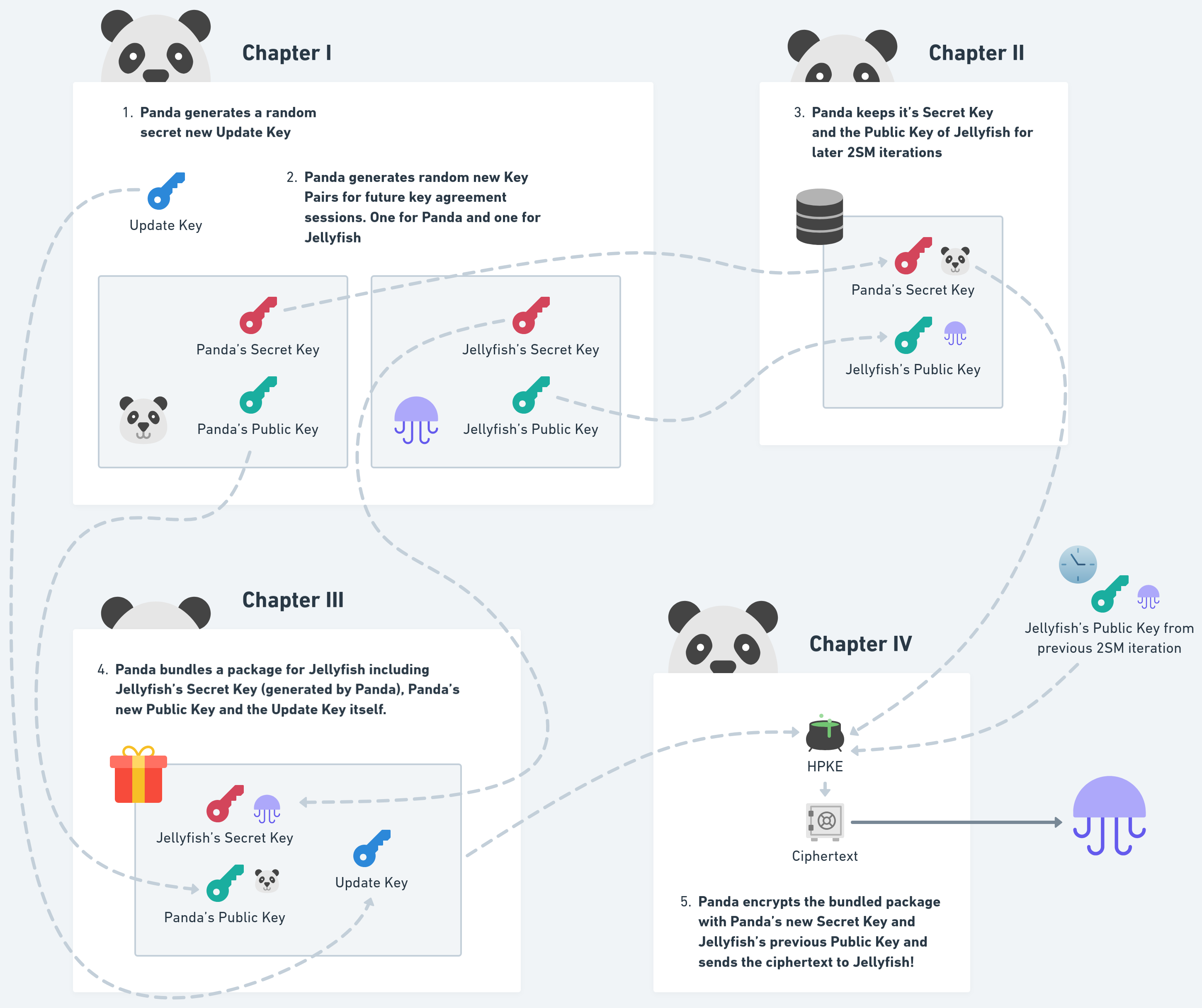

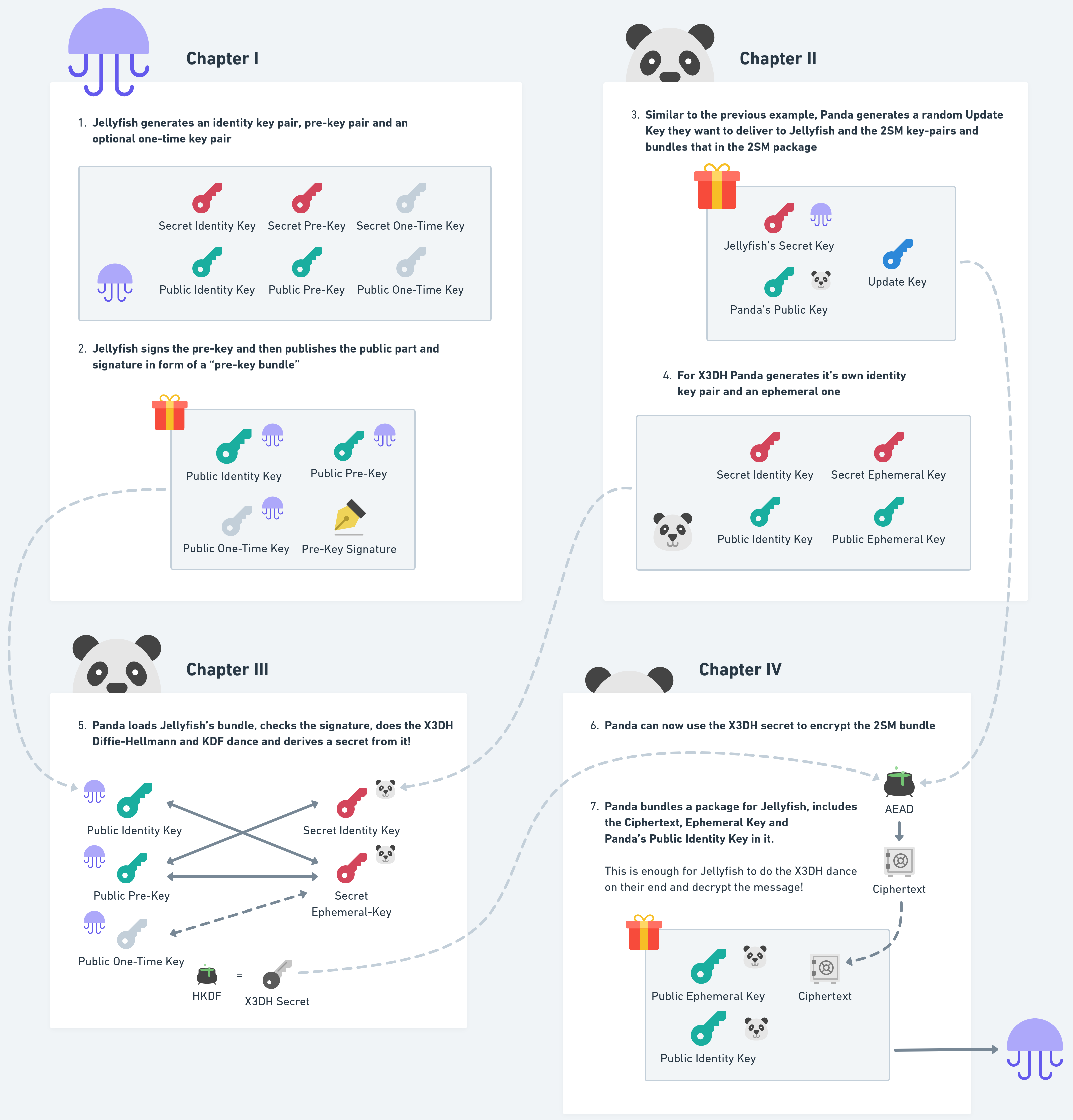

The 2SM key agreement protocol used by p2panda combines a X3DH key handshake with subsequent key rotations realised with a simpler public key encryption scheme (HPKE).

In p2panda-encryption we randomly generate a secret key we can later use as the symmetrical secret to encrypt to all members in the group or to derive the message ratchet “root chain key” for one member.

To make a group aware of a new secret key we could encrypt the secret pairwise with public-key encryption (PKE) towards each member of the group, resulting in an O(n^2) overhead as every member needs to share their secret with every other. The DCGKA paper proposes an alternative approach which they call “Two-Party Secure Messaging Protocol” (2SM) where a member prepares the next encryption keys not only for themselves but also for the other party, resulting in a more optimal O(n) cost when rotating keys. This allows us to “heal” the group in less steps after a member is removed.

The 2SM protocol is well described in the DCGKA paper (Appendix D) and we’ve made a little diagram to show you the process:

Panda uses 2SM to securely deliver an “Update Key” to another member, the Jellyfish. Panda uses the Public Key of Jellyfin to encrypt this information. They learned about that Public Key from previous 2SM iterations. Next to the “Update Key” Panda will also send them new key material for the next, future 2SM iteration. This is the special trick of this protocol!

For encrypting the key towards each member a Hybrid Public-Key Encryption Scheme (HPKE) is used with DHKEM_X25519, HKDF_SHA256 and AEAD_AES_256_GCM as parameters. Since we only use the secrets for key agreement once per iteration we can make 2SM forward secure.

In case we’re trying to establish a secret key for the first time though, we need to look closer into the “Key Handshake” Phase. This is where the X3DH protocol of Signal comes into play, which was designed to establish a secure future communication channel between two parties, even when one of them is offline.

The 2SM protocol works the same during the handshake phase, the only thing which is different is how we encrypt the secret towards the other member, by using X3DH instead of HPKE.

For our “Message Encryption” scheme we make one-time pre-keys mandatory during X3DH to ensure strong forward secrecy while in our “Data Encryption” scheme we remove that requirement and only use pre-keys which can be rotated after a while and published based on the application’s security model.

p2panda Data Encryption

In p2panda-encryption we implement a simple and secure, symmetrical key encryption for application data with the forward-secure 2SM key-agreement protocol and post-compromise security on manual key-rotation or member removal.

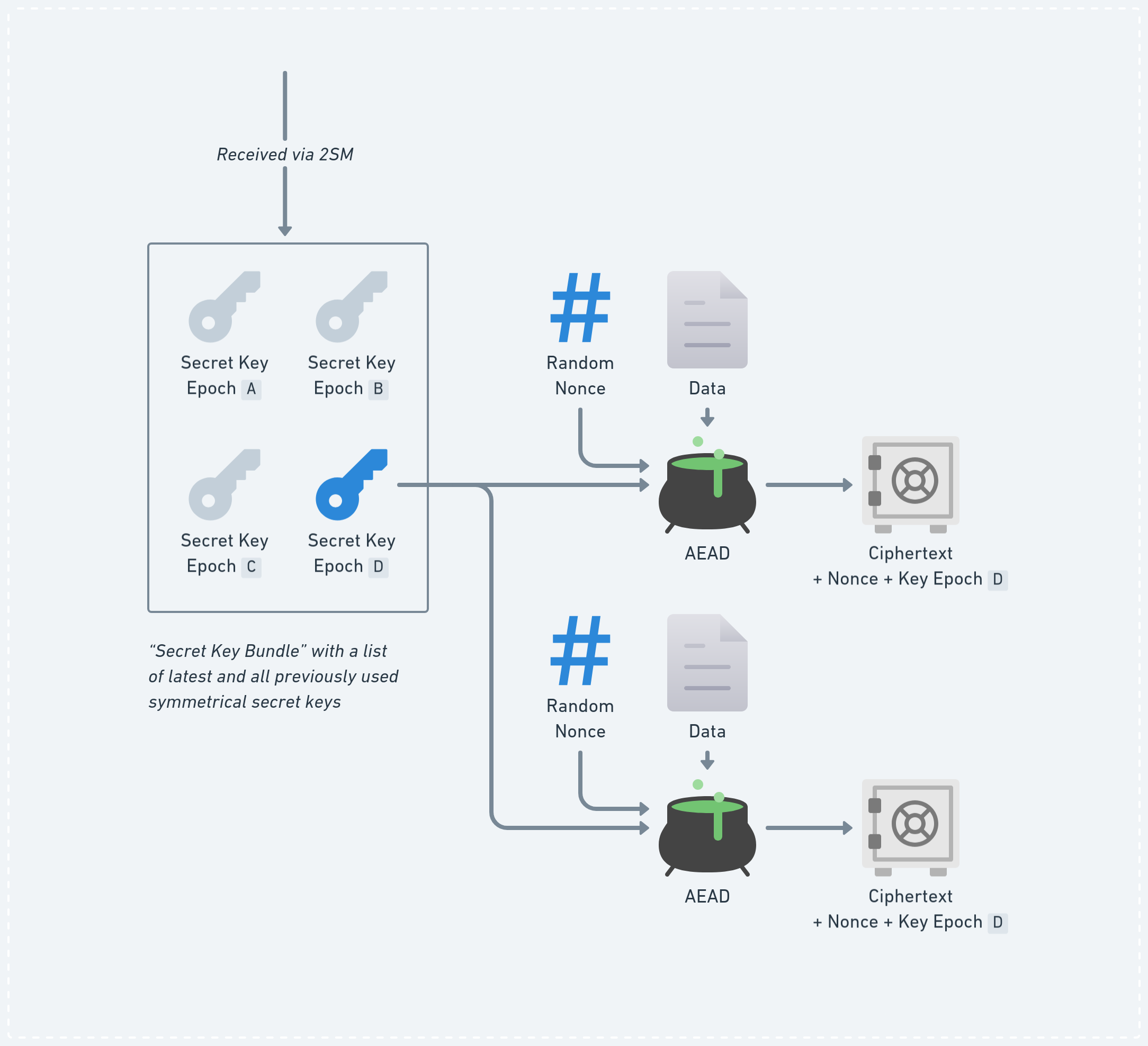

Every member in the group uses the same secrets to encrypt the data. During key agreement we include a list of all previously used secrets and send it to the new members so they will be able to decrypt all previously created data even when they entered the group later. It would be possible to use a more efficient way of storing previously used keys in the future, for example in form of a Cryptree.

For encryption we use the latest key and for decryption we keep a list of all currently known (current and past) keys. Keys are identified with an “epoch” hash. We’re using a unique hash to identify the key, derived with a Sha256 Hashed Message Authentication Code (HMAC)-based key derivation function (HKDF) from the secret, as there might be cases where group members concurrently generate new keys and a simple number counter would not be sufficient to distinctively identify them.

While the secret symmetric key didn’t get rotated, we continue re-using it for each data encryption (each time with a different nonce).

For symmetrical encryption of the application data we use XChaCha20-Poly1305, an authenticated encryption with associated data (AEAD) symmetric-key encryption scheme with randomly generated 24 byte nonces. Nonce-reuse is catastrophic in AEAD but preventing it is hard in a decentralised setting, so it is usually recommended to keep state around to understand which nonce to use next. By using XChaCha20-Poly1305 we can drop the requirement to keep that state around, since the nonces are large enough to be generated randomly and securely.

Every encrypted data includes the ciphertext and additional metadata, including the key hash (epoch) and nonce that have been used to encrypt the data.

During the initial key-agreement handshake via X3DH we don’t use one-time pre-keys and only rely on signed pre-keys. The forward secrecy is defined by the lifetime of the pre-keys which again is set by the application developers. This is only the case for the handshake, afterwards we’re back at strong forward secrecy provided by the 2SM protocol.

p2panda Message Encryption (with Double Ratchet)

For encryption with strong forward secrecy we’re implementing Signal’s Double Ratchet algorithm as specified by the DCGKA paper.

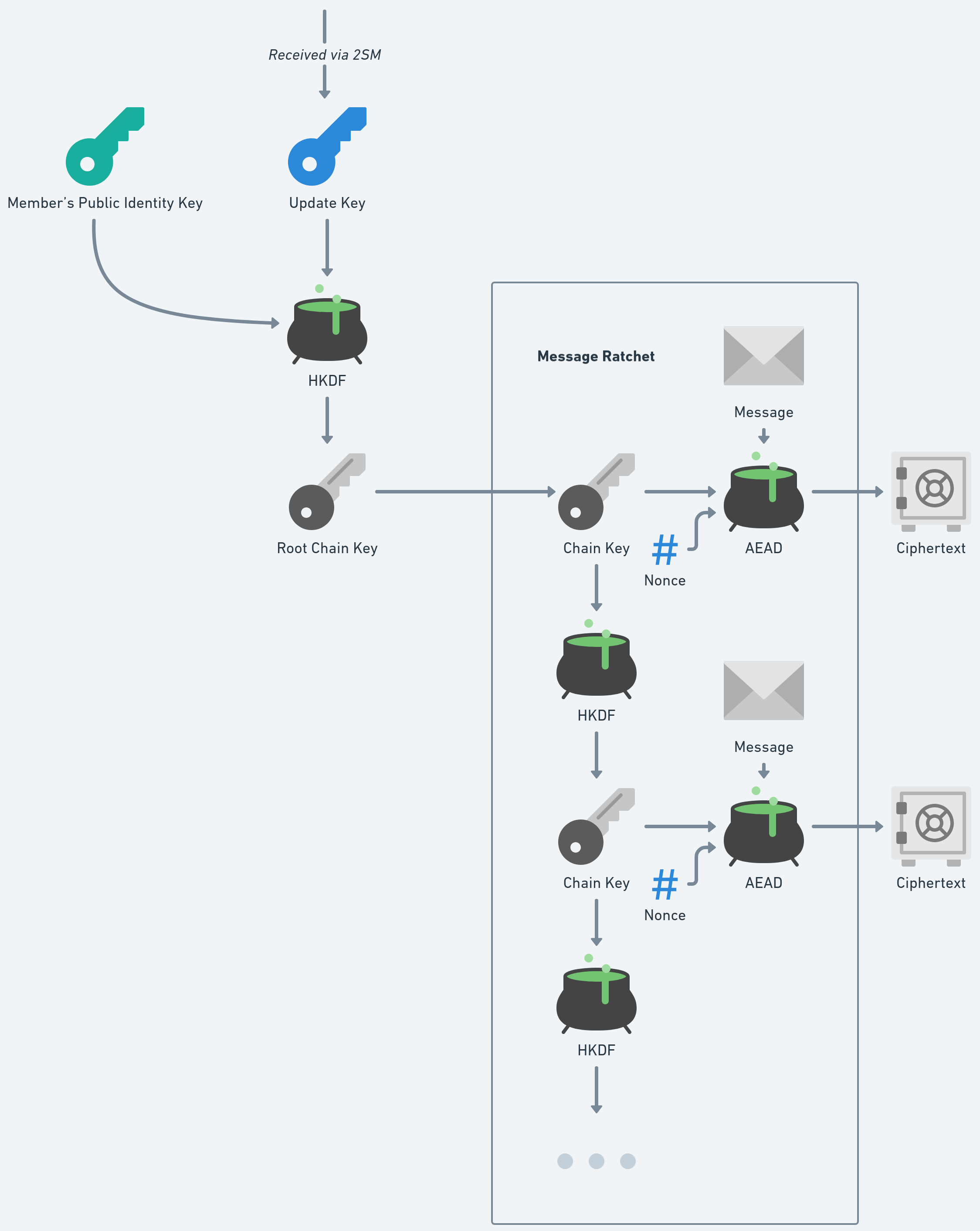

After the “update key” of randomly generated 32 bytes got delivered pair-wise via 2SM to each member in the group, we can establish the regarding message ratchets towards each member of the group by deriving the initial “root chain key” via a HKDF with the member’s public identity key.

The sender keeps an “outgoing” message ratchet to each member. The receiver will keep an “incoming” message ratchet with the same state. Like this they will be able to derive the same chain key for that message to finally decrypt it. This means that each member in the group needs to keep an incoming and outgoing message ratchet for each other member in the group!

For the message ratchet we use a pseudorandom function (PRF) with a Sha256 HKDF scheme. The encryption of message data itself is done with AES-256-GCM AEAD, with the chain key and a nonce derived from the used chain key itself (using the same derivation function).

Additional care is required to make sure that all peers update their ratchets in the same order. The important mechanism here is an explicit “acknowledgement” for each rotated update key. Acknowledgements are also “group operations”, similar to member additions or removals, etc., where the sender confirms that they have observed and applied a key update. By learning that another peer has confirmed the newly rotated secret we can switch our message ratchet towards them with that new key. Another great “side effect” of the acknowledgements is that we can learn how far the group progressed in it’s post-compromise security.

Another important point to mention are concurrent cases where a member might learn too late that they have been added to a group, even though some messages have already been sent to them. These senders need to actively send them the missing ratchet update keys; a process called “forwarding” in DCGKA. Another case is when two members independently added another member each: Alfie adds Charlie at the same logical time as Betty adds Davie. In this situation Charlie will end up not knowing about Betty’s new ratchet state; as soon as Betty realizes that they will have to send the update again to Charlie.

These cases are handled as part of the DCGKA protocol specification from the paper (see section “6.2.5 Handling Concurrency”).

Integration with p2panda stack

Since our implementation of p2panda-encryption is in Rust, we express many parts of the group encryption in the form of “traits” or generic interfaces, allowing developers to adjust certain parts. For example, customising the group management CRDT for their own needs or using a different key agreement protocol while keeping the same encryption algorithm. We will also offer a way for developers to deliver their own storage solutions for secret key material and group state.

p2panda-encryption is agnostic to p2panda itself, no concrete data-types, sync or ordering strategy or transport is assumed by the implementation.

For use with the rest of p2panda though we will provide Rust Stream implementations in p2panda-stream for both giving the required causal ordering of group operations and the encryption and decryption of application data or messages itself.

Like this developers can easily “stack” different stream iterators on top of each other and not need to worry about encryption from this point on, as the data they will receive from these iterators will be ordered, buffered, dependency-checked and decrypted automatically.

We will also provide a p2panda message “header extension” and sync protocol solution where almost no metadata needs to be revealed. This will be developed this Summer as we’re about to look into efficient DAG- and set-reconciliation sync strategies.

The group membership CRDTs are also very useful outside of the encryption system. We can use membership as a way to represent roles. For example, we can ask now: “Is Billie part of the moderator group?”. Being part of an encryption group can also mean having “read” permission. Nodes will not sync data with another peer if they don’t have this permission - and even if they would receive the data, they would not be able to decrypt it.

See you soon and thank you!

As already mentioned, an implementation is currently underway and to-be-released in Spring 2025! You can subscribe to our RSS feed for new upcoming posts on our website or follow us on the Fediverse to get informed when p2panda-encryption is ready for use.

We want to especially thank the Cryptographic Engineer and OpenMLS maintainer Jan Winkelmann from Cryspen for answering our questions around the cryptographic parts of our implementation and the Researcher Erick Lavoie for giving advice and ideas for efficient group membership CRDT designs. We took inspiration from work done by Abhilash Mendhe during his Master studies at University of Basel, under the guidance of Erick. We also want to thank the authors of the “Key Agreement for Decentralized Secure Group Messaging with Strong Security Guarantees” paper for giving a strong foundation of future p2p group encryption solutions and lastly NLNet for supporting this adventure and our security audit of Radically Open Security.